Introduction

On May 15 of each year, Palestinians observe “Nakba Day.” “Nakba” is Arabic for “catastrophe.” This is how many Palestinians describe the founding of the State of Israel, Israel’s victory against invading Arab forces in the 1948 war, and the subsequent refugee crisis. There were an estimated 500,000 to 750,000 Palestinian Arab refugees. Most fled to escape the war, which was launched by Arab forces. A minority were expelled by Israeli forces or left because Arab leaders encouraged them to do so. The refugees suffered personal and collective traumas that remain central to Palestinian identity to this day. This suffering was made worse by Arab states, which used the refugees as political weapons in the conflict with Israel. Another group also became refugees in the aftermath of the 1948 war. An estimated 850,000 Jews living in Arab states fled or were expelled. Arab governments engaged in brutal retaliation against these Jewish communities after Israel’s victory in 1948, even though their Jewish citizens lived far from the war zone and had virtually no involvement in the fighting. The Jews fled from Arab states in the 1950s and 1960s, so by the 1970s, only 1 percent of the Jewish population remained in Arab states. By the 1980s most Jews were gone from Iran as well. For the Jews from Arab states and Iran, this, too, was a catastrophe.

Historical Background

Over 3,000 years ago, the Jewish people built a thriving civilization and culture in the land of Israel. Over time they were conquered by a series of foreign empires. In 70 CE, the Roman Empire crushed the Jewish kingdom of Judea in response to a Jewish rebellion. After Roman legions mercilessly crushed another Jewish uprising in 135 CE, Rome changed the name of Judea to the province of Syria-Palaestina.

While some Jews remained in their homeland in communities like Jerusalem, Hebron, and Tiberius as well as throughout the Galilee, most gradually scattered across the Middle East and Europe. Those who remained became a minority in their own land, which would eventually be conquered and colonized by various Christian and Islamic empires.

Although Jews flourished in certain times and places outside of Israel, they endured centuries of persecution and brutal violence. In the late 1800s, Jews started the Zionist movement, hoping to overcome the oppression they faced in Europe and the Middle East by creating a free, independent nation in their ancestral home. They began moving back to Palestine, where the ancient kingdom of Judea once stood, joining Jews who were already there and building new communities.

From 1517 to 1917, Palestine was divided into several districts within the Islamic Ottoman Empire. It was inhabited by a mix of Arabs, Bedouins, Jews, Turks, and other groups. Arabs were the majority. Many arrived with various conquering empires over the centuries, while others were descended from locals who had converted from Judaism and Christianity.

Some Arabs also immigrated in the 19th and 20th centuries to pursue economic opportunities, including those created by the growing Zionist movement. Though Jews were a minority, they had maintained an unbroken, continuous presence in the land for 3,000 years and were the largest ethnic group in the city of Jerusalem by 1860. With a total population of roughly 300,000, there was more than enough room in Palestine to create a Jewish state without displacing Arabs or others.

In 1920, three years after the British defeated the Ottomans (who sided with Germany) in World War I, the League of Nations (an early version of the UN) established the British Mandate of Palestine. The terms of the Mandate officially recognized the rights of the Jewish people in their homeland. Britain was required to govern the territory and help Jews create a “national home” while protecting the rights of all other groups living there. However, by that time Arabs developed a nationalist movement of their own, and their leaders strongly opposed Jewish immigration and selfdetermination in Palestine. Initially, they demanded the creation of a large Arab state combining Syria and Palestine (referring to Palestine as “Southern Syria”). Later, they shifted focus to demanding an exclusively Arab state in Palestine alone. As such, the Arab–Israeli conflict began as a clash between Zionists, who wanted to create a Jewish state in their ancestral home (with backing from the League of Nations), and Arab nationalists, who saw Jews as foreign colonizers and insisted that all of Palestine should be another Arab state. The first shots were fired in 1920, when Haj Amin alHusseini—a Palestinian Arab leader appointed by the British authorities—incited violence against Jews in Jerusalem. Similar attacks ensued in 1921 and 1929, when the Jews of Hebron were massacred and forced to flee their homes.

In the decade that followed, the conflict escalated further. Jewish leaders expressed a willingness to negotiate and split Palestine, despite being promised the entire territory for their national home by the League of Nations. However, Arab leaders rejected the creation of a Jewish state in any part of the land. In 1939, on the eve of World War II, when Jewish refugees from Europe were desperately searching for an escape from Nazi oppression, the British government turned fully against Zionism in order to appease Arab nationalists. It issued a “White Paper” that effectively blocked Jewish immigration to Palestine while denying Jewish refugees’ entry to Britain itself. As a result, millions of Jews were trapped in Europe, vulnerable to the Nazi genocide. The conflict came to a head in 1947 when the UN proposed a two-state solution, calling for the creation of a Jewish state and an Arab state. Jewish leaders accepted the compromise, but Arab leaders rejected it and launched a civil war to prevent the establishment of a Jewish state.

“The representative of the Jewish Agency told us yesterday that they were not the attackers, that the Arabs had begun the fighting. We did not deny this. We told the whole world that we were going to fight.”2

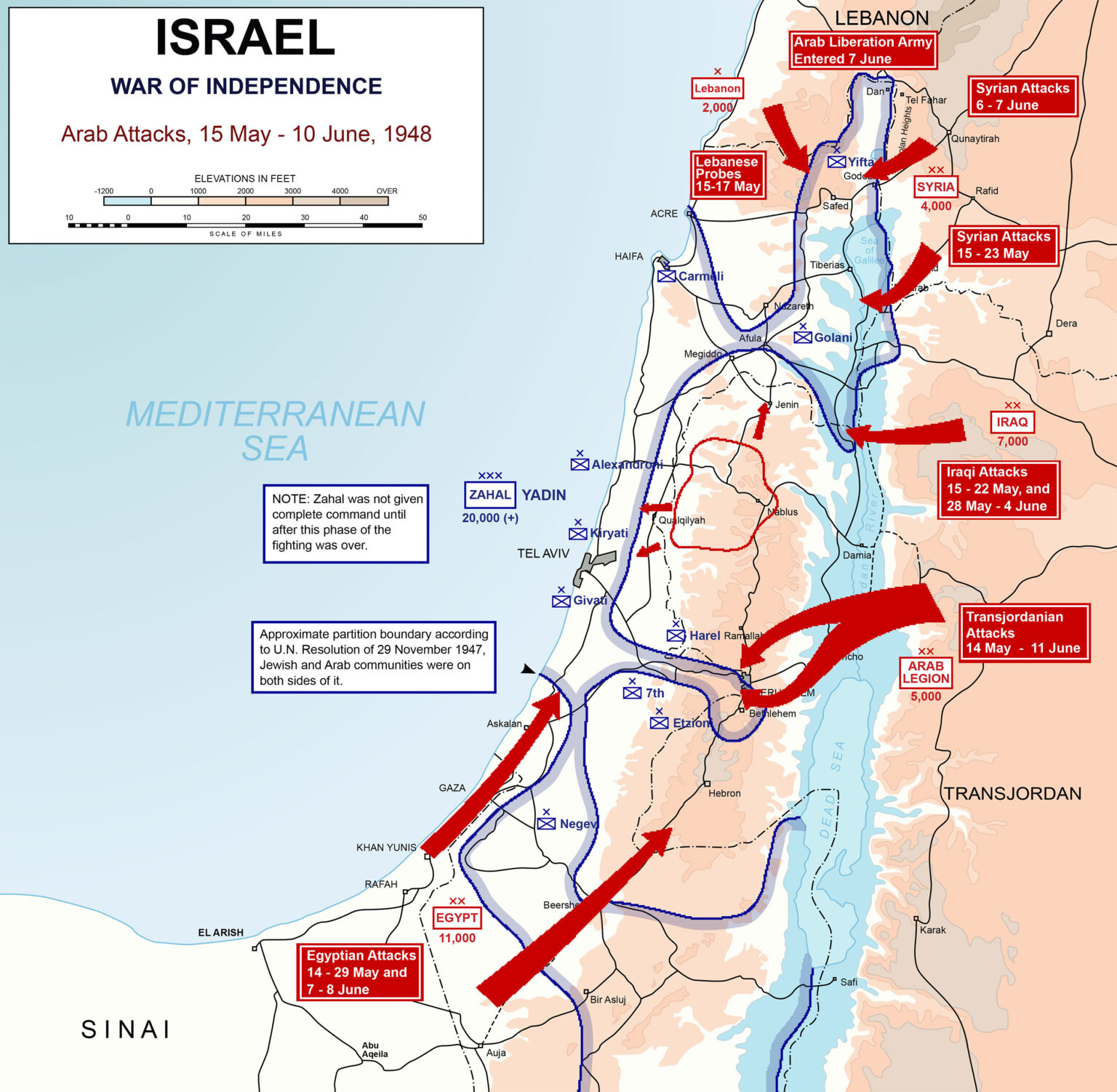

Amidst this civil war, on May 14, 1948, the State of Israel declared independence. The next day, May 15, 1948, five Arab states invaded Israel with the declared intention of destroying it. Hence, the date chosen for Nakba Day (May 15) is the anniversary of a massive invasion by Arab forces. The decision by Arab and Palestinian leaders to launch this war of aggression was catastrophic. It left thousands dead on both sides, and it led to between 500,000 to 750,000 Palestinian Arabs and over 850,000 Jews from Arab states becoming refugees.

This will be a war of extermination and momentous massacre which will be spoken of like the Tartar massacre or the Crusader wars.

Causes of the 1948 Palestinian Refugee Exodus: The Nakba

Many Palestinian nationalists falsely claim that once the UN voted for the compromise partition plan, “Zionist gangs” immediately began expelling Palestinians in a premeditated plan.6 Reality, however, is far more complex. According to historian Benny Morris, “transfer or expulsion was never adopted by the Zionist movement or its main political groupings as official policy at any stage of the movement’s evolution—not even in the 1948 War.”7 Indeed, 165,000 Palestinian Arabs chose to remain in Israel and became citizens. The rest became refugees due to a variety of factors.“[T]he Palestine refugee problem was born of war, not by design, Jewish or Arab. It was largely a byproduct of Jewish and Arab fears and of the protracted, bitter fighting that characterized the first Israeli–Arab war; in smaller part it was the deliberate creation of Jewish and Arab military commanders and politicians.” 8

The Main Reasons Palestinian Arabs Fled

Palestinian Arab leaders were among the first to flee—even before the war.

Many Palestinian nationalists falsely claim that once the UN voted for the compromise partition plan, “Zionist gangs” immediately began expelling Palestinians in a premeditated plan.6 Reality, however, is far more complex. According to historian Benny Morris, “transfer or expulsion was never adopted by the Zionist movement or its main political groupings as official policy at any stage of the movement’s evolution—not even in the 1948 War.”7 Indeed, 165,000 Palestinian Arabs chose to remain in Israel and became citizens. The rest became refugees due to a variety of factors.

Refugees fled heavy fighting in populated areas.

This was a civil war, and combat occurred everywhere. Palestinian Arabs were able to flee to safety in Arab territories. Israeli Jews, on the other hand, literally had their backs to the sea with no place to take refuge.

Arab radio stations broadcast exaggerated accounts and false rumors of Jewish atrocities.

According to Hazem Nusseibeh, an editor at the Palestine Broadcasting Service in 1948, “We weren’t sure the Arab armies for all their talk were really going to come. We thought to shock the population of the Arab countries to stir pressures against their governments.” 10 The broadcasts however, had the opposite effect. Nusseibeh explained to theBBC 50 years later, “This was our biggest mistake. We didnot realize how our people would react … Palestinians fledin terror.”11 This is corroborated by another source, refugee Yunes Ahmed Assad, who told a Jordanian newspaper in 1953, “The Arab exodus from other villages was not caused by the actual battle, but by the exaggerated description spread by Arab leaders to incite them to fight the Jews.”12

Reasons Why a Minority of Refugees Left

Overconfident Arab leaders encouraged them to leave.

“Since 1948 we have been demanding the return of the refugees to their homes. But we ourselves are the ones who encouraged them to leave. Only a few months separated our call to them to leave and our appeal to the United Nations to resolve on their return.” 13

— Haled al-Azm, Syrian Prime Minister, 1948–1949

Israeli troops encouraged or forced people to leave, particularly from areas that Arab forces used for attacks.

An example is the infamous and tragic case of Deir Yassin, which occurred in the context of an Israeli effort to break the Arab siege of Jerusalem, which had put 100,000 Jews at risk of starvation. Deir Yassin was an Arab village that Arab troops used as a base for attacks. Israeli forces attempted to capture the village, leading to a battle in which many Palestinian Arab civilians were killed, and all residents were expelled.

“Israeli forces did on occasion expel Palestinians. But this accounted for only a small fraction of the total exodus, occurrednot within the framework of a premeditated plan but in the heat of battle, and was dictated predominantly by ad hoc military considerations (notably the need to deny strategic sites to the enemy if there were no available Jewish forces to hold them).” 14

— Professor Efraim Karsh

Arab radio stations broadcast exaggerated accounts and false rumors of Jewish atrocities.

According to Hazem Nusseibeh, an editor at the Palestine Broadcasting Service in 1948, “We weren’t sure the Arab armies for all their talk were really going to come. We thought to shock the population of the Arab countries to stir pressures against their governments.” 10 The broadcasts however, had the opposite effect. Nusseibeh explained to theBBC 50 years later, “This was our biggest mistake. We didnot realize how our people would react … Palestinians fledin terror.”11 This is corroborated by another source, refugee Yunes Ahmed Assad, who told a Jordanian newspaper in 1953, “The Arab exodus from other villages was not caused by the actual battle, but by the exaggerated description spread by Arab leaders to incite them to fight the Jews.”

Atrocities, Expulsions of Jews by Arab Forces During the 1948 War

According to Morris, there were expulsions of Jews during the war as well: “Palestinian militiamen who fought alongside the Arab Legion consistently expelled Jewish inhabitants and razed conquered sites. … All the Jewish settlements conquered by the invading Jordanian, Syrian, and Egyptian armies … were razed after their inhabitants had fled or been incarcerated or expelled.” 15 In the case of the Etzion Bloc, the Jewish defenders were massacred as they were surrendering.16 In Jerusalem’s ancient Jewish Quarter, all Jews who survived the fighting were expelled by the Transjordanian Arab Legion.17Israeli troops encouraged or forced people to leave, particularly from areas that Arab forces used for attacks.

An example is the infamous and tragic case of Deir Yassin, which occurred in the context of an Israeli effort to break the Arab siege of Jerusalem, which had put 100,000 Jews at risk of starvation. Deir Yassin was an Arab village that Arab troops used as a base for attacks. Israeli forces attempted to capture the village, leading to a battle in which many Palestinian Arab civilians were killed, and all residents were expelled. “Israeli forces did on occasion expel Palestinians. But this accounted for only a small fraction of the total exodus, occurred not within the framework of a premeditated plan but in the heat of battle, and was dictated predominantly by ad hoc military considerations (notably the need to deny strategic sites to the enemy if there were no available Jewish forces to hold them).” 14 — Professor Efraim KarshArab radio stations broadcast exaggerated accounts and false rumors of Jewish atrocities.

According to Hazem Nusseibeh, an editor at the Palestine Broadcasting Service in 1948, “We weren’t sure the Arab armies for all their talk were really going to come. We thought to shock the population of the Arab countries to stir pressures against their governments.” 10 The broadcasts however, had the opposite effect. Nusseibeh explained to theBBC 50 years later, “This was our biggest mistake. We didnot realize how our people would react … Palestinians fledin terror.”11 This is corroborated by another source, refugee Yunes Ahmed Assad, who told a Jordanian newspaper in 1953, “The Arab exodus from other villages was not caused by the actual battle, but by the exaggerated description spread by Arab leaders to incite them to fight the Jews.”After 1948, Jordan illegally occupied Judea, Samaria, and

eastern Jerusalem. It renamed these areas the “West Bank”

because they are west of the Jordan River. Jordanian

authorities prohibited Jews from visiting their holiest sites in

Jerusalem for 19 years. This lasted until Jordan attacked Israel

in the 1967 war and Israeli forces fought back and took control

of the city.

Meanwhile, most Palestinian Arab refugees were not allowed

to return to their homes after the bitter fighting ended in 1949.

Israel offered to take in families that had been separated

during the war, pay compensation for any loss of private land,

and absorb 100,000 refugees in return for peace. Arab states

rejected this offer, hoping they would be able to defeat and

destroy Israel in the years to come.18