Israel Facts

BOOKLET SERIES ISRAELPOCKET FACTS Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share on whatsapp Share on email View as PDF If you want

BOOKLET SERIES

JUSTICE & REBIRTH

FOR A HISTORICALLY

OPPRESSED PEOPLE

“His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing nonJewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

The Balfour Declaration (1917) was a groundbreaking British government statement that recognised the profound connection of the Jewish people to the land of Israel/Palestine. It was a landmark achievement for Zionism — the liberation movement of the Jewish people, who sought to overcome 1,900 years of oppression across Europe and the Middle East and regain selfdetermination in their indigenous lands.

The Balfour Declaration promised that the British government would use its “best endeavours” to promote the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” while also safeguarding “the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine”.

Jews are indigenous to Israel, the birthplace of their identity, language, religion and culture. The Jewish people’s physical, historical and spiritual connection with the land of Israel has been unbroken for over 3,000 years.

Independent Jewish rule in Israel existed intermittently for over a millennium until the first century, when Imperial Rome crushed a series of Jewish rebellions.

After crushing the third of these revolts, Imperial Rome renamed the country “Syria Palaestina” in a bid to destroy the indigenous Jewish link to the land. However, this colonial name change never took hold among Jews. The Romans also sought to destroy Jewish culture by outlawing Judaism, executing major rabbinic figures and banning Jews from Jerusalem and renaming it Aelia Capitolina. Hundreds of thousands of Jews were killed and many more were enslaved and scattered across Europe and the Middle East, but a minority remained. Arch of Titus in Rome, depicting Roman victory over the Jews. Early Hebrew script from a 2,700-year-old artifact found in Israel.

The Jewish presence in the country was unbroken even up to modern times. Until the fourth century, Jews were the majority in the Galilee and Golan regions. Archaeology and historical texts testify to the continuous presence of Jewish communities in all four Jewish holy cities of Jerusalem, Hebron, Tzfat (Safed) and Tiberius as well as in scattered communities throughout the rest of the country.

The Jewish people retained a tenacious connection to the land of Israel and in particular to Jerusalem, which is often referred to as “Zion”. Thousands of Jewish texts express this profound yearning to rebuild Jerusalem and regain Jewish independence. This has been a constant since Jews were dispossessed of their land right through to modern times. These ideas are expressed in daily prayers, which are said facing Jerusalem, and the annual Passover Seder always ends with the entreaty, “Next year in Jerusalem!

The land of Israel never became the sovereign territory of any other nation but was governed by a series of pagan, Christian and Islamic imperial powers — Rome, the Byzantine Empire, Sassanids, Arabs, Saladin, sultan of Egypt who defeated the Crusaders in the land of Israel. Ancient Jewish fortress of Masada, located in Israel. Umayyads, Abbasids, Fatimids, Seljuks, Crusaders, Ayyubids, Mamluks and Ottomans.

Throughout these centuries groups of Diaspora Jews fled persecution abroad and returned home, joining the Jews who had remained in the land.

At the start of Ottoman imperial rule in 1516, there were around 10,000 Jews living in the Tzfat (Safed) region alone. These communities were boosted by a steady trickle of Jews arriving from Eastern Europe in the late 18th century and from Yemen a century later. In 1864 the British Consulate in Jerusalem estimated a Jewish majority in the holy city, and Jews have remained the majority population in Jerusalem to this day.1

In 19th-century Europe a “new” racial form of anti-Semitism arose, which was grafted onto existing classic religious anti-Semitism. This became a permanent and intractable fact of European life, eventually inspiring the Nazis in the 20th century.

Zionism, a modern Jewish movement, was launched in the late 19th century to liberate Jews from this lethal racism and re-establish their independence in their homeland. The movement grew rapidly, gaining a large following throughout the Jewish world by the 1890s.

The first significant wave of modern Zionist immigration from Europe (the First Aliya) occurred in the early 1880s. By 1917 Zionism was a mature Jewish liberation movement that had increased the Jewish population of Palestine (the Yishuv) to nearly 100,000, about 15 per cent of the total population.

Many Jews who went back to their homeland during this period were fleeing pogroms, discrimination and poverty in Russia and Eastern Europe, particularly in the decade prior to the First World War, 1904 to 1914 (the Second Aliya)

1 Cited in Gold, Dore. The Fight For Jerusalem, Regnery Publishing. p. 120 (2009). The British Consul estimated 8,000 Jews, 4,000 Muslims and 2,500 Christians.

In the 19th century Palestine was a backwater of the Ottoman Empire and was divided into three separate administrative zones. It was largely barren and in some regions barely habitable. Poverty and disease were rife and economic activity minimal. Mark Twain travelled through parts of it in 1867 Residents in the region of Palestine, 19th century. Theodore Herzl speaking to the first Zionist Congress. and found a “desolate country whose soil is rich enough, but is given over wholly to weeds… a silent mournful expanse… a desolation…. We never saw a human being on the whole route. [There was] hardly a tree or shrub anywhere”.

During this period Palestine was home to around 300,000 people, drawn from a diversity of ethnic groups, including Arabs, Jews, Circassians, Druze, Kurds and Europeans. The majority Muslim, Arabicspeaking population included some who had lived in the region for generations as well as immigrants from Algeria, Egypt, Syria and Libya and nomadic Bedouin.

Modern political Zionism — the liberation movement of the Jewish people — was neither created by the Balfour Declaration nor granted any special legal status by it. By 1917 the Jewish national home was already being rebuilt in Palestine by Jewish visionaries fighting for justice and the rights of their people, not on behalf of any colonial power.

The backdrop to the Balfour Declaration was the immensely chaotic period during and after World War I. The end of the war Founding of Tel Aviv, 1909. brought about the dissolution of the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, German and Ottoman empires.

The downfall of the great European and Ottoman empires opened the way for many nationalist movements to press their claims, as national self-determination became the basis of the post-war order. (See maps below)

This included nationalist movements of various peoples from the Middle East, including Arabs, Persians, Kurds, Assyrians and Berbers. It also included the Jews, who were already returning to rebuild and reclaim their historic homeland. (See maps below)

The Balfour Declaration was the first step in gaining international recognition for Jewish rights in what is now the state of Israel. By itself the declaration was not a concrete policy or law. It was merely a promise by Britain to undertake “their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement” of a “national home for the Jewish people”.

At the San Remo Conference in 1920, the League of Nations adopted the wording of the Balfour Declaration, including its recognition of “the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine”. It enshrined the collective rights of the Jewish people to self-determination in Palestine under international law, embedded until The surrender of Jerusalem to the British. today through Article 80 of the UN Charter.

The British Mandate for Palestine was created on territory comprising modern Israel, Gaza, the West Bank and Jordan. The British government was made legally responsible for helping the Jews re-establish their national home in this land. (See 1920 map below.)

In 1922 Britain divided the Palestine Mandate to create the Arab territory of Transjordan, which today is the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. (See 1922 map below.) Modern Iraq and Syria were also created during this period, under the administration of the British and French. The map of the entire Middle East was transformed after the fall of the Ottoman empire.

Similar processes occurred in Europe, as Czechoslovakia, Armenia, Finland, Lithuania, Poland, Latvia, Estonia, Ukraine and Georgia emerged from the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires.

During the transformation of the Middle East, Kurds, Assyrians and other non-Arab minorities also sought independence and self determination but were betrayed by colonial powers. Britain surrendered to the demands of Turkish and Arab nationalists, leaving Kurds, Assyrians and other peoples stateless

During World War I Britain also made The League of Nations. ambiguous promises to Arab nationalist leaders, which were interpreted by some as conflicting with the Balfour Declaration. The British government later clarified that these promises did not include Arab control over Palestine, but the initial ambiguity helped to sow the seeds of conflict.

Britain was far from alone in its support for Zionism, which was simply the Jewish equivalent of movements that rose across Europe and later the Middle East. Declarations similar to Balfour were made by France, Germany, Turkey and the USA regarding other territories during the same period.

The principle of self-determination was widely regarded, especially by the United States, as the natural and fair successor to the old colonial order after World War I. Because of this widespread support, the right of all peoples to self-determination was included in the San Remo Treaty and ultimately enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations. Zionism was and remains a Jewish liberation movement that epitomises the universal right to self-determination.

Israel’s legitimacy under international law is based on the same treaties that led to the creation of many nations across the Middle East and Europe after World War I. To question the legality of Israel’s existence is to question the legality of the United Nations Charter and all states that came into being during that era.

Initially, the reaction of Arab leaders was unenthusiastic but not universally hostile. Within Palestine the influential Nashashibi clan was more moderate in its approach to Zionism than its chief rival, the militant alHusseini clan.

In Arabia, Emir Faisal reached an agreement with Jewish leader Chaim Weizmann in 1919 that placed relations between the Arab and Jewish peoples on a peaceful and cooperative footing. Faisal sent a letter declaring, “We will wish the Jews a most hearty welcome home”. But Faisal later withdrew his support due to pressure from pan-Arab nationalists.

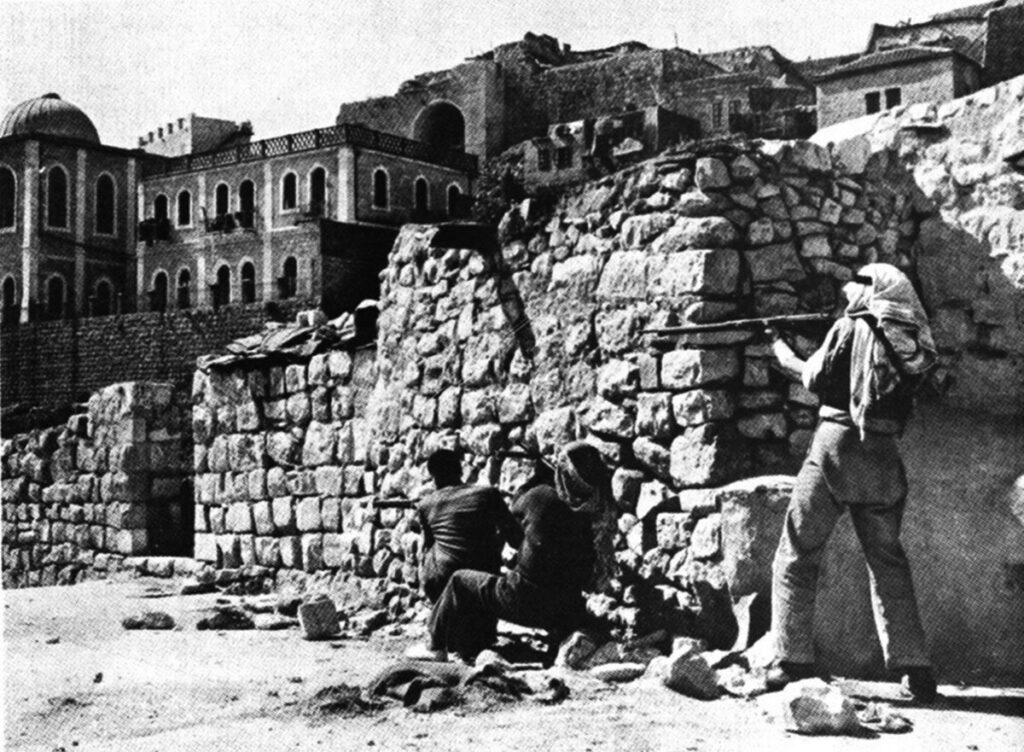

By 1920 Arab nationalist resentment at Jewish efforts to reconstitute their national homeland led to murderous anti-Jewish riots throughout Palestine. This violence initiated the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and was instigated primarily by Haj Amin al-Husseini, a leader of the al-Husseini clan. Shortly thereafter, the British appointed him grand mufti of Jerusalem, making him the de facto leader of the Arabs in Palestine.

The real tragedy of the Balfour Declaration and the Palestinian Mandate was not in their conception but in their execution. Despite the growing horror of the Holocaust, Britain reneged on its moral and legal obligations to both the Jewish people and the international community. In an attempt to stop the escalating racism, supremacism and antiJewish violence of the Nazi-aligned Haj Amin al-Husseini, the British government retreated from its previous support for Jewish rights and national aspirations.

The first sovereign entity to be established by the British in the Palestine Mandate following the San Remo Treaty was not a Jewish state but an Arab state — Transjordan. It was created with encouragement from the USA in 1922 on 78 per cent of the territory of the original Palestine Mandate. (See maps 5 and 6.) Although this division of land was a distortion of the mandate’s stated purpose — to establish a Jewish homeland in the entire territory — most of the Jewish leadership reluctantly accepted it.

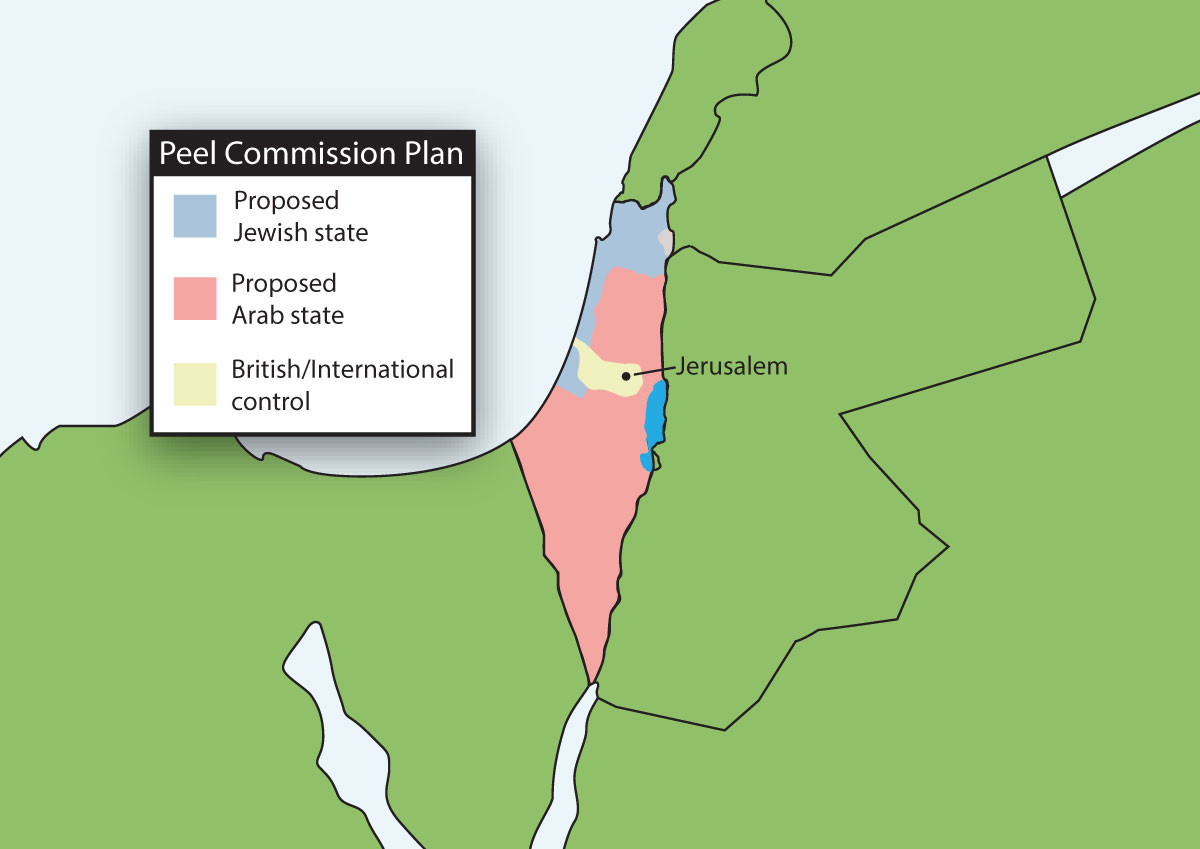

By the 1930s British policy toward the Jews had hardened. In response to the al-Husseiniled Arab revolt, which began in 1936, supported by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, the British government proposed a second partition of the remaining Palestine Mandate. It sought to create a Jewish state on approximately 20 per cent of the remaining land and a second Arab state on approximately 80 per cent. (See map 7.) The Jewish leadership was dissatisfied but agreed to negotiate. The Arab leadership rejected the existence of a Jewish state in any territory, and Britain ultimately repudiated the proposal. This was the first of many instances in which Palestinian leaders refused to recognise Jewish rights to self-determination and rejected the opportunity to create an independent state for their people.

On the eve of World War II, Jews were desperately trying to flee Nazi terror in Europe, and the world was closing its doors to them. Despite the impending horror, Britain issued the 1939 White Paper, severely restricting Jewish immigration to Palestine. A limited number of Jews were to be allowed in for five years, after which immigration would be completely cut off. At the same time, al-Husseini, the Palestinian leader installed by the British, was collaborating openly with the Nazis at the highest levels.

The real tragedy of the Balfour Declaration and the Palestinian Mandate was not in their conception but in their execution. Despite the growing horror of the Holocaust, Britain reneged on its moral and legal obligations to both the Jewish people and the international community. In an attempt to stop the escalating racism, supremacism and antiJewish violence of the Nazi-aligned Haj Amin al-Husseini, the British government retreated from its previous support for Jewish rights and national aspirations.

The first sovereign entity to be established by the British in the Palestine Mandate following the San Remo Treaty was not a Jewish state but an Arab state — Transjordan. It was created with encouragement from the USA in 1922 on 78 per cent of the territory of the original Palestine Mandate. (See maps 5 and 6.) Although this division of land was a distortion of the mandate’s stated purpose — to establish a Jewish homeland in the entire territory — most of the Jewish leadership reluctantly accepted it.

The legal term “disproportionate force” does not refer to equivalence in casualties or weaponry but to military actions that cause more civilian harm than is warranted by the military gains. Knowing that civilians always suffer from wars, Israel has practiced restraint despite Hamas’ relentless attacks against Israeli citizens, though most countries would not tolerate even one rocket attack. Israel has been widely praised for attempting to minimize harm to Palestinian civilians during military operations by warning of impending attacks, aborting operations if civilians are in target zones, and ensuring delivery of humanitarian goods. Israel’s policies prompted British military expert Col. (ret.) Richard Kemp to testify that Israel does more “to safeguard the rights of civilians in a combat zone than any other army in the history of warfare.” Conversely, Israel’s terrorist enemies use Palestinians as human shields, fight from civilian centers, and target Israeli civilians, tragically increasing civilian casualties.

As the Holocaust unfolded, the British navy intercepted and turned away scores of emergency rescue ships filled with desperate Jewish refugees escaping the killing fields of Europe and seeking safety in Palestine. This callousness resulted in the needless loss of countless lives.

Britain abandoned Jewish rights, in violation of the terms of the mandate given to it by the League of Nations in the San Remo Treaty. This emboldened Arab extremists in Palestine who supported this agenda and radicalised a minority of the Jewish population, leading to even more intense conflict on the ground.

By 1947 the British decided to end the mandate and turned the matter of resolving the conflict over to the United Nations.

On 30 November 1947 the UN, seeking a peaceful compromise, passed Resolution 181, calling for a “Jewish state” and an “Arab state”. The Jewish leadership accepted the proposal, but Arab and Palestinian leaders rejected it, vowing to prevent Jewish statehood through violence.

Attacks on Jewish civilians by Palestinian Arab fighters began immediately. The Arab League met and decided to reject peace and follow a military solution, initiating a bloody civil war. “Volunteer” Arab forces from Syria, Iraq, Libya and Egypt entered Palestine to fight the Jews. They laid siege to Jerusalem, nearly starving 100,000 Jews to death there.

As the war unfolded, Britain adopted an increasingly anti-Jewish stance, handing military hardware to Transjordan’s Arab Legion, led by British Officer Sir John Glubb, seeking to ensure a complete Arab takeover of Palestine.

The British Mandate of Palestine officially ended on 15 May 1948. Israel had declared independence the day before, and the Arab states immediately invaded with the intention to destroy the Jewish state. After months of heavy fighting, Israel overcame the Arab states’ aggression and emerged victorious. This first Arab-Israeli war is remembered as the War of Independence by Israel and as the “Nakba”, meaning “Catastrophe”, by Palestinians.

There were an estimated 450,000 to 750,000 Palestinian Arab refugees who fled the war First Israeli Prime Minister David Ben Gurion declares independence. British officer Sir John Glubb. to Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, the West Bank and Gaza. There were some instances of Israeli expulsions but this was not preplanned or part of a systematic policy. The majority of the refugees fled of their own accord to avoid being trapped in the war zone created by Arab states.

In all areas where Arab forces were victorious, such as eastern Jerusalem, Gush Etzion, all Jews were forced out of their homes or massacred. The Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem’s Old City was emptied, and every synagogue was destroyed. From 1949 to 1967 Jordan occupied eastern Jerusalem and the regions of Judea and Samaria, which they renamed the “West Bank”.

During the 20 years after the 1948 war, over 850,000 Jews were expelled or fled from Arab states, where many had lived for millennia. Unlike the Palestinian Arabs, none of these Jews fled a war zone. Rather, they faced mounting discrimination and persecution — often violent — forcing them to flee as stateless refugees. Arab governments confiscated almost all their property, leaving most of them impoverished. When they were purged from the Arab lands, most of these Jewish refugees sought refuge by returning to Israel — their ancestral homeland. They became the majority of the country’s Jewish population and have been integral in shaping Israel’s development, politics, society and culture.

1. Jews are indigenous to Israel. Portraying them as colonisers is a slanderous and dehumanising denial of Jewish history and identity.

2. The Balfour Declaration — issued during the First World War in anticipation of the imminent dissolution of the Ottoman Empire — did not create the Zionist movement, nor did it invent the idea of a Jewish national home in Palestine; both of these were already well established long before 1917. It was, however, of significance in generating momentum for international recognition of the Jewish people’s struggle for liberation and self-determination in their historic homeland.

3. In contrast to the rapid creation of new Arab states after World War I, Jewish selfdetermination was delayed for another generation at immeasurable cost to the Jewish people. The gradual abandonment of British support for Jewish rights was a cynical response to the racism and supremacism of key Arab leaders, who used violence both to deny Jewish selfdetermination in any part of Palestine and to intimidate Arabs who were willing to compromise with the Jews.

4. After 1,900 years of dispossession and persecution across Europe and the Middle East, the creation of Israel was a long overdue act of justice for a historically oppressed people.

5. Zionism and the Balfour Declaration are not the primary causes of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or of Palestinian suffering. Arab and Palestinian leaders could have averted decades of bloodshed by recognising Jewish rights and making difficult compromises for peace, and they can still do so today. It is not too late to achieve a just peace and build a better future for Israelis and Palestinians alike.

Avalon Project: “The Palestine Mandate”, New Haven, CT, Yale Law School, 2008, www.avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/ palmanda.asp

Dershowitz, A., The Case for Israel., Hoboken, NJ, Wiley and Sons, 2003

Fromkin, D., A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East, New York, Owl Books, Henry Holt and Company, 1989

Gilbert, M., Exile and Return: The Struggle for a Jewish Homeland, Philadelphia and New York, J. B. Lippincott Company, 1978

Betrayal of the Jews, Hatikvah Films, 2014: www.youtube.com/ watch?v=0LgKJ5HzSQ0&feature=youtu.be

Karsh E., Palestine Betrayed., New Haven, CT/ London, Yale University Press, 2011

Laqueur W., Rubin B. The Israel-Arab Reader, London, Penguin Books, 2008

Schneer J., The Balfour Declaration, London, Bloomsbury, 2010

Shapira A., Israel – a History, London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2014

YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY

BOOKLET SERIES ISRAELPOCKET FACTS Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share on whatsapp Share on email View as PDF If you want

BOOKLET SERIES ANSWERING TOUGH QUESTIONS ABOUT ISRAEL Common accusations against Israel and answered with factual, direct and concise answers. Share on facebook Share on twitter

BOOKLET SERIES THE JEWISH PEOPLE A Beautiful Tapestry Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share on whatsapp Share on email View as